Starring Jules (third grade debut) Read online

TITLE PAGE

DEDICATION

TAKE ONE: street-fair leftovers, babysitters with titles, and other things that keep you up at night

TAKE TWO: gooey omelets, firm handshakes, and invisible lies

TAKE THREE: recess calisthenics, heavy squinting, and other extracurricular activities

TAKE FOUR: small plates, dummy lessons, and rotten surprises

TAKE FIVE: Florida calling, waxing poetic, and good strong library smells

TAKE SIX: gummy shoes, doctors without orders, and sitcom-y solutions

TAKE SEVEN: colorful behavior, the drama of the eight-year-old, and a good time to bring up tubers

TAKE EIGHT: breakfast for dinner, made-for-TV brothers, and favorite things

TAKE NINE: deep breaths, pushy reviewers, and coming attractions

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ALSO AVAILABLE

COPYRIGHT

How You Can Tell You Are Getting Old:

The first day of third grade (and not second grade) is tomorrow.

One of the third-grade teachers used to be your numero uno best babysitter ever.

You got a different third-grade teacher.

Your little brother is going to kindergarten.

You have a job.

I put my notebook away and look out the window at the bright night. It is 8:06 p.m. and still light out and I am supposed to be going to sleep early. But there was a street fair today and the air still smells like lamb and peppers and roasted corn on the cob with queso fresco. Ay! How I miss my second-grade teacher, Ms. Leon, already!

Big Henry is snoring on the other side of the curtain and I wonder how he can sleep at a time like this. There is so much to think about. It took me almost an hour to lay out my first-day-of-school clothes all because it is going to be 300 degrees outside, which isn’t corduroy weather at all. Instead, I have to wear shorts (rainbow) and a tank top (with a good-looking green apple on it), which is really more like camp clothing. It is very hard to get in a back-to-school mood without corduroy.

But Big Henry doesn’t mind any of this. He is happy that he gets to wear the same mesh shorts he’s worn every day since May. The only new thing he’ll be wearing is a note card pinned to his shirt with his classroom and teacher written on it. I wish I had a note card to wear. If I did, it would say: If this child is lost in a third-grade classroom, with a teacher who probably doesn’t understand her, please return her to kindergarten, where she will color and learn her letters and where she will not be picked up after school by a car service that will take her to a TV studio in midtown. Instead, she will ride home on a scooter and eat snacks on the roof.

I tiptoe past Big Henry’s giant snoring self and out into the living room. My mom looks at me.

“Didn’t we already do this once?” she asks.

“Do what?” I ask, even though I know what she means. We’ve said good night several times. I even interrupted my dad at his restaurant several times to say good night.

“Jules.”

“Mommy.”

“It’s going to be a fun day tomorrow, and afterward, we’ll go for ice cream,” she says.

“No, that’s the problem. After school is a Look at Us Now! rehearsal, so no first-day-of-school ice cream. I mean, it’s not a problem, it’s just a thing.” I am careful not to say anything is a problem when it comes to being on a TV show. Otherwise, I will get the this-is-your-choice speech my mom or my dad makes every week or so.

“So we’ll have ice cream after that,” she says. “See? Problem solved. Go to bed.” I sit down next to her. “What is it, Julesie? You have one more chance before I actually get angry.”

“It’s Mr. Santorini,” I say. “Mister,” I say again. “I’ve never had a boy teacher before and I heard he’s really weird and gives tons of homework.”

“He’s not a boy teacher, Jules. He’s a man, and he isn’t weird. He’s quirky. There’s a difference,” my mom says. “And just because people say something about him doesn’t mean it’s true. You need to see for yourself. Besides, his name is the same as a beautiful Greek island with turquoise water and white-sand beaches and all the lamb and peppers you like so much at street fairs. Picture that when you meet him tomorrow.”

“I just wish I could have had Avery,” I say.

“That wouldn’t have been fair and you know it. She’s like family. And don’t forget, Jules. At school, she’s Ms. Kaplan.”

I snort at this. How am I supposed to call a girl who does yoga headstands on my bed while blasting rap music Ms. Kaplan?

“Anyway,” my mom says, “at least they kept the four of you together.”

By “the four of you,” my mom means Elinor, my best friend forever whose beautiful British accent makes everything better every day; Charlotte, my ex–best friend forever, who acts like a gigantic snob most of the time but who sometimes is nice by accident; Teddy Meant-to-Be Lichtenstein, who still calls me by my Periodic Table of Elements name, and who will definitely find a whole bunch of new ways to bump into me every day; and me. The lucky ones who did not get Mr. Looks-Like-Lamb-and-Peppers Santorini are Abby and Brynn, who will be spending their time with a certain yoga-posing teacher who will probably have pizza parties at least once a week. Or maybe tapas parties. Tapas are small plates of food. Avery loves tapas.

“Right,” I say to my mom. “The four of us.”

“Bed, Jules.”

“What time is it?” I ask.

“8:20,” she says.

“What time exactly?” I ask. The exact time is important.

“8:19.”

“Perfect.”

“Why?”

“Because that gives me eleven minutes to fall asleep at an even number.”

My mom shakes her head and shoos me away. I stop to look at my brother, who is asleep with his hands behind his head. Suddenly, he opens his eyes for one second, yells “I WANT LEMONADE!” at the top of his lungs, and closes his eyes again.

I run over and hop onto my bed and laugh hysterically into my pillow. He was probably dreaming about the lemonade lady at the street fair. He was so thirsty after bouncing on the giant bouncers he whined about lemonade until we finally got to the lady who sings her lemonade jingle all day so you can find her easily. I was thinking she should be on TV with that voice and that jingle, and not me with my boring old fizzy-milk jingle.

I look out the window again. Finally the sky is getting dark and my clock says 8:24. Six minutes left to fall asleep. Six minutes until second grade is officially over and I am a third grader with a kindergartner brother, a third grader with a brand-new teacher who probably doesn’t like rap music, a third grader with a job as the sassy little sister on a TV show that probably everyone in the world will watch.

I never see 8:30 on the clock, which means — and this is a bad thing — I must fall asleep at a very odd time.

Big Henry is up at the crack of dawn and all I can do is put my pillow over my head and hope he doesn’t come jump on me. I hear him whisper-yell my name —

“Jules!”

He has worked very hard on getting rid of his lisp all summer long and now I feel a little bit sad that it is mostly gone, especially when he says my name. I don’t respond to him, though, because I am not ready for the day. I hear him run down the hall toward my parents and our first-day-of-school breakfast selection.

I want to go back to sleep for a few more minutes, but I can’t close my eyes. I am picturing a breakfast buffet of yogurt parfaits, and waffles with cream, and sliced tomatoes piled high with giant slices of mozzarella cheese, like the ones they have at Mother’s Day celebrations at fancy restaurants. I get up and walk toward th

e kitchen.

“Hey, where’s my tomatoes and cheese?” I ask.

“I’m sorry, Julesie,” my dad says. “I couldn’t get to the place with the good mozzarella, so today omelets will have to do.”

“Omelets are gross,” I say.

“Jules!” my mom says now. “How about you try that again?”

“Omelets are a little bit gross?” I ask. “Like, gross in the best possible cheese-oozing-out-of-the-sides kind of way?”

My mom narrows her eyes at me. “I’m assuming you’re nervous about the first day, but try and be positive. It’s Henry’s first day, too, you know.”

“Kindergarten!” he yells, and egg flies out of his mouth and halfway across the kitchen in celebration. I feel like I’m going to throw up at this — the only thing grosser than cheese oozing out of an omelet is egg bits flying out of your little brother’s mouth.

“Jules,” my dad says, “to make it up to you, I’ll put tomatoes inside your omelet. The eggs will be good for your brain. They make you think.” My dad has a way of turning every food into something very important. If I tried to keep a list of things he says about food, it would go on and on and on until forever, starting with:

“Only eat things fresh from local organic farms.”

“The darker the chocolate the better.” (Even if it’s so dark it stops tasting like chocolate and starts tasting like the wood chips under the swings in Central Park.)

“The sweet potato is a real gem of a tuber.” (Tuber is a very grown-up, organic-chef word for a vegetable that grows underground. I plan to impress my new teacher with this word.)

Then there would be about thirty gazillion more things on the list about tart cherries and coconut milk and the sleep benefits of kiwi fruit and pumpkin seeds. And then the list would end one day a long, long time from now, with my father’s favorite reason why people should eat this way: “So we can all live to be 350 years old and take walks down Broadway arm in arm with our great-great-great-great-grandchildren.”

I think it would be okay to live only until maybe 225 and occasionally eat some milk chocolate, but I never say that to him. I just smile and eat kale-and-tomato omelets.

After we get all dressed up in our first-day-of-school clothes, we kiss my dad good-bye and head downstairs in the elevator. In the lobby, Joe the doorman high-fives us and Big Henry shows off.

“Let’s see those karate-chopping break-dance moves,” Joe says. He loves Big Henry. Everybody does. And it’s because if someone asks Big Henry to do his karate-chopping break-dance moves, he just starts doing it, with no music or anything, and with a backpack filled with brand-new school supplies on his back.

If someone asks me to show off my moves — moves like, I don’t know, thinking too much or maybe singing on a countertop on a TV show — I always find a leg to hold on to like I’m still in nursery school. I think my third-grade resolution is to one day show off my moves just like Big Henry does, smack in the middle of everything.

“An apple for the teacher — I like it, Jules,” Joe says to me when Big Henry’s dance show is over.

I smile at him and wave, but I don’t know what he’s talking about. “Your shirt,” my mom says to me once we’re on the street. “People always say you should bring an apple for the teacher, so I guess that’s what Joe thought you were doing by wearing that shirt.”

“It wasn’t,” I say. “But will that make him like me?”

“He’ll like you because you’re you, Jules. Apple or no apple.”

I don’t really believe her so I’m very glad I have the apple just in case.

Some things happen when we get to school:

Big Henry doesn’t cry.

He doesn’t hold on extra tight to my mom’s hand and beg her not to leave.

He doesn’t ask her to double-check to make sure she has packed the right three-ring binder, the 1 1/2-inch one that was listed on the kindergarten school supplies list they sent home with classroom assignments.

When my mom pulls him back to her for one last hug, he wiggles out of it and says, “Okay, okay, I have to go!”

Mom and I just stand there staring at him as he walks through the very same doors that have practically scared the breakfast out of me every single first day of school for the last three years, like it’s nothing.

“Don’t be sad, Julesie,” my mom says now.

“I’m not,” I lie.

“You wanted to walk him into Ms. Kim’s room, right? You wanted to be the big kid on the block walking your little brother in there and giving your old kindergarten teacher a hug, right?”

“I guess,” I say, and I shrug. I still hate it when I shrug. I wish I could get my body to forget how to shrug. “Well, gotta go,” I say.

“No hug?” she says. “You don’t have to show off for Big Henry. I’ll tell him you didn’t need a hug, either.”

I hug her tight. “That would be a lie,” I say.

“A teeny-tiny white lie,” she says.

“Almost invisible,” I say.

“I can live with it,” she says.

I’m smiling and walking through the door when my mom says, “Remember it’s not going to be a perfect day.” I look around to make sure no one heard her say that, and even though no one does, my face burns up anyway. I walk inside and find my way to Mr. Santorini’s third-grade classroom, crossing everything but my eyes hoping he doesn’t hate me.

I walk in and something strange is going on. No one else is in the room. Not even the teacher. Not even Charlotte, who is always first to everything. I feel the butterflies rev up in my belly and I try to calm them by finding my cubby and unpacking my backpack. The best part of arriving for the first day of school is pulling out of your brand-new rainbow-striped backpack the perfect black-and-white marble notebook and a box of pointy, sharpened pencils, ready for freewriting.

“Oh, hello there!” I hear behind me, and I turn around to see Mr. Santorini and a whole pack of kids filing in behind him. I feel like there’s a spotlight shining on me. And not in a good way.

“Hi,” I say quietly, making sure not to open my mouth so wide that little diced omelet tomatoes come flying out.

“I grabbed the early birds who were here for a quick run down the hall to get some nervous first-day energy out.” Then he turns back to the small group and says, “Ten-hut!” and clicks his shoes together so loud my belly drops to my feet. My friends look at each other. “We’ll get to that later, sailors.”

I feel my mouth hanging open a little and close it quickly. Early birds? A quick run in the hallway? Sailors? This Mr. Santorini feels like a character on Look at Us Now! and not like a real-life teacher at all.

“Jules!” Elinor breaks the weird silence and comes over to me. “Look, we’re sitting next to each other!”

“Ah! Bloom, Jules,” Mr. Santorini says, looking at a list he’s holding in his hand. He walks over to me with his hand out. “Very nice to meet you.” When I look at him closely, I realize he looks a little bit like Captain von Trapp from The Sound of Music, if Captain von Trapp would ever wear a Hawaiian shirt, that is. I’m just hoping he doesn’t have a whistle.

I put my hand out and let him shake it. “Hmmm,” he says. “Let’s try that again. This time when I shake, shake back, sailor.” I know what he means about the shake because this is how Colby Kingston, my agent, shakes hands. I just didn’t know it was okay to shake a teacher’s hand this way. I also don’t know why he’s calling me “sailor.”

“Very nice to meet you,” Mr. Santorini says again.

I grab on and shake firmly this time. I also stand up a little straighter and clear my throat. I feel like my TV character, Sylvie, would handle all of this better than I am handling it, and I also think that this quirky Mr. Santorini would like Sylvie, my sitcom character, better than Jules Bloom, or Bloom, Jules — worm-digging Upper West Sider.

“Likewise,” I say with gusto — gusto is a script word — shaking his hand hard. Sylvie always says things like �

�likewise,” and I always wonder who would actually say something like this in real life, but I realize now that my new third-grade teacher, who calls people “sailor” and says last names first, is definitely someone who says “likewise.”

“Okay, then,” he says, and turns back to the others, who have started making their way to their seats.

“Where’s Charlotte?” I ask Elinor when we sit down. She shrugs at this, which makes me happy because even my completely cool and calm very best friend shrugs sometimes. Even she talks with her shoulders when she doesn’t know what else to say.

“She’s coming late,” Teddy says.

“Lichtenstein, Theodore,” Mr. Santorini says.

I snort into my hand at this as Mr. Santorini shows Teddy to his seat.

“Hi, Teddy,” Elinor says when Teddy falls into the chair next to hers, and I realize I’m glad Teddy and I are separated by a whole person. “How do you know she’ll be late?”

“Teddy always knows everything,” I say. And he does. He’s like the guy on the radio show that wakes me up in the morning. He knows the weather, the news, and whatever happened on TV last night. And he apparently knows that Charlotte Stinkytown Pinkerton, former best friend, and current not-as-terrible-as-I-thought sort-of friend, is going to be late for the first day of third grade. “So why is she late? Charlotte’s never been late for anything, and especially not the first day of school.”

“I saw her last night at the diner and she said she had an appointment they can’t change. That’s all I know,” Teddy says.

Elinor and I look at each other. Very suspicious. Who has an appointment on the first day of school?

At last, Mr. Santorini clears his throat and we all quiet down. “Welcome to third grade,” he says. “Third grade is run like a tight ship, sailors. We will respect each other, be well behaved, and we will be curious and brave. This ship is sailing to wonderful, far-off places where fiction and facts meet; where every piece of writing will have a beginning, a middle, and end; where we will multiply and divide; and where we will get to know each other and some new people, too, through biographies …”

Starring Jules (Super-Secret Spy Girl)

Starring Jules (Super-Secret Spy Girl) Starring Jules (third grade debut)

Starring Jules (third grade debut) Starring Jules (In Drama-rama)

Starring Jules (In Drama-rama) Izzy Kline Has Butterflies

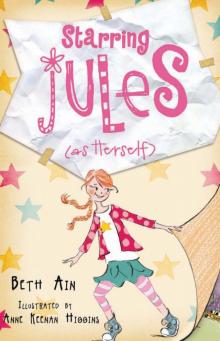

Izzy Kline Has Butterflies Starring Jules (As Herself)

Starring Jules (As Herself)