Starring Jules (third grade debut) Read online

Page 4

My perfect vision and I wake up early and go back to the not-perfect third grade. At school, we spend the morning in the library during our scheduled time and we get to look at more books to decide who we want to be. The thing that has me mad is that the people who already know who they’re going to be get to start their research, which means Teddy, for one, has a very big head start. We have two more days to decide and then it has to be approved by the third-grade teachers in case the person isn’t appropriate or in case you chose the same person as someone else. Apparently, two Sacagaweas is one Sacagawea too many.

Teddy is hard at work on his da Vinci project and I am feeling very jealous that he is so excited. I don’t feel that way about anyone I read about. I mean, I like the Helen Keller story, but I’m definitely not a good enough actress to play her; and I really like Florence Nightingale because her life was very exciting, but then I picture all that blood and sickness and my head starts to spin; and then I think I might like to be Teddy Roosevelt, since my dad is OBSESSED with Teddy Roosevelt and always makes us stop and look up at the big statue of him on his horse at the Museum of Natural History. But I don’t think I’m a good enough actress to be a man. I can’t even be a ventriloquist’s dummy.

“How about Eleanor Roosevelt, then?” Elinor asks.

“Who’s that?” I ask.

“She’s the one with the statue in Riverside Park,” Elinor says. “Plus, her name’s Eleanor!”

“Teddy Roosevelt was her uncle,” Teddy says.

“How do you know these things?” I ask.

“Why do you think my name is Teddy?” he asks.

“Wow,” Elinor says. “Are you a Roosevelt?” she asks.

“I’m a Lichtenstein,” he says, and we all laugh. “But we’re big fans of the Roosevelts. And Eleanor Roosevelt did a lot of interesting things, according to her statue in the park, but she wasn’t a mathematician like da Vinci, and a scientist and an artist and a physicist, and —”

“We aren’t listening anymore, Teddy.” It’s Charlotte and her glasses talking. And I want to be annoyed with both her and the glasses for talking this way to Teddy, since I am the only one who is really allowed to talk to Teddy this way, but then I remember that he called her Stinkytown this week, so he kind of deserved it.

“Who are you choosing, Charlotte?” I ask, realizing that she has been very, very private, which means she’s up to something.

“Not telling you, Jules. You’ll just steal it.”

“I will not,” I say.

“Yes, you will, because it’s the best one to do,” she says.

Elinor and I look at each other and say at the same exact time, “Who?!!”

“Jinx,” Teddy says, never looking up from his pile of da Vinci books. And we are all quiet for a good, long time after that.

Mr. Santorini comes over to us after a while and says, “How’s it going, kiddos?”

I feel stuck, because I really shouldn’t talk since Teddy never released me from the jinx, but I SHOULD answer my teacher. I look at Teddy, who is deep in his book now and not paying attention. I think he forgot about the jinx!

“Going that well, huh?” he asks again.

“It’s going well, Mr. Santorini,” Charlotte the unjinxed says now. “There are so many people to choose from!”

Elinor and I look at each other and I watch her give Teddy a little push to remind him.

“Hey, no pushing!” he says, before realizing that Mr. Santorini is standing there watching.

“No pushing is right, Elinor,” he says. “That’s a yellow for a warning.” I gasp out loud since I don’t even care about the jinx anymore now that Elinor has gotten punished for something Teddy did!

Elinor’s face twists up a little, so when we line up to go back to class I grab her hand. “Are you okay?” I ask, but she just shrugs in a way that looks like tears are coming, and the one thing I absolutely can’t watch is a crying Elinor. The only other time I saw her cry was when she told me about her summer with her dad and how her parents were actually getting divorced — DIVORCED! And I just didn’t want her to ever feel that sad and I hate feeling like there isn’t any way to make someone feel better.

“Don’t cry,” I say. “Yellow isn’t that bad.”

“What’s worse?” she says.

I think for a second. “Red!”

She smiles. “I was just trying to get Teddy to say our names three times,” she says.

“Did you hear that, Teddy?” I say. “You got Elinor in trouble.”

“I think I might throw up,” he says. Teddy always thinks he’s going to throw up when he gets nervous, which is why it is VERY hard to stay mad at him. “I just forgot. I was reading about da Vinci and I forgot!”

I look at Elinor and realize that I want her to forgive Teddy so he doesn’t actually throw up. That would make everything much worse.

“It’s fine,” she says, but she doesn’t look fine, and I see her staring at the yellow flag on her name for the rest of the day. I wish she would just go over to Mr. Santorini and explain the jinx so he would turn her back to green, but she doesn’t. And she doesn’t participate at all, which she always does because she’s so smart and confident and always raises her hand. I am so mad at Mr. Santorini. If there’s one person in the entire world who should never, ever get a bad-behavior flag it is Elinor.

At the end of the day, we walk out together and I ask if she’s going to tell her mom.

“That’s the thing,” she says. “If I tell her, she’ll probably tell my dad, and I don’t want him to think I’m doing a bad job in school. I was kind of hoping he’d even come to the wax museum.”

“Tell her that,” I say. “And maybe she’ll let you have an almost-invisible lie just this once.”

“What’s that?” she asks, smiling.

“It’s the kind of lie that doesn’t hurt anyone, and it can even help people,” I say, thinking of how I got the hug from my mom on the first day and that helped me and it didn’t hurt Big Henry NOT to know about it.

“Thanks! We’ll see what she says. But I like it!” She seems happy for the first time since the yellow flag, so I am very relieved. I just wish I could make her parents’ divorce invisible.

In the car service on the way to rehearsal, I ask my mom why she’s never told me about this da Vinci guy, since she’s an artist and everything.

“Oooh, Leonardo da Vinci was really something, Jules. He was a little bit of everything.”

“Seems like he was a lot of everything,” I say, thinking about all those things Teddy was saying about him.

“Yes, I guess he really was. He’s what you call a Renaissance man. Is that who Teddy chose?”

“How’d you know?” I asked.

“Because he’s kind of a lot of everything, too,” she says. “I think da Vinci’s a great choice for him.”

I think about Teddy and his nervous throw-up face and I shake my head. “Teddy Lichtenstein, Renaissance Man,” I say seriously, in my TV-voiceover voice, and my mom and Big Henry and I all laugh. It’s a funny thought.

“I want a playdate,” Big Henry says.

“You had a playdate yesterday,” I say. “With your new friend Marco, remember?”

“Stop talking like I’m a baby,” Big Henry says.

“Hank!” my mom says.

“You are still kind of baby,” I say. Then my little baby brother kicks the seat in front of him just as we get to the studio, and my mom hustles him into the babysitting room while I go find my sitcom family.

Jordana and John McCarthy come running over with excited faces.

“What? No glasses?” John McCarthy asks.

“Nope,” I say. “Just my plain old face. No glasses.”

“Your face is not plain,” Jordana says. “Are you bummed out?” she asks with her Southern drawl. She sounds so nice when she talks. And this reminds me of Elinor and her nice accent and her love of sports and how those are her things. And then I think of Charlotte and her

pink polka-dot glasses and her big opinions and how all of that is her thing, and then I think of Teddy and his smart brain and how that’s his thing, and all of this makes me feel that lost feeling I had in the library after the wax museum announcement.

Plain old lost.

“You know,” John McCarthy says, “on sitcoms there’s always a solution to every problem, and the solution always happens within twenty-two minutes.” I love having a sitcom big brother. I wish I had a real-life big brother who would say very smart things all the time.

Jordana stares at him. “You know, John McCarthy, you’re right,” and when she says right it sounds like this: raaaaght. “What if we ask the writers to give Sylvie glasses?”

“Is that possible?” I ask, suddenly very excited.

“Maybe, baby,” Jordana says. And all I can think as we march ourselves over to the writers’ table is that I want a sweatshirt that says I Heart Jordana.

When we get to the table, the writers don’t look up. They always have their noses in a script and they are always drinking coffee, and it is not the tall-icy kind of coffee. It is the piping-hot kind with little hand protectors on the cup. It could be one million degrees outside but writers would drink piping-hot hand-protector coffee no matter what.

“Sorry, kids. No can do on the glasses this season, but maybe we’ll think about it for next season if all goes well.”

“If all goes well” reminds me that Look at Us Now! will be on TV this Sunday night and that there will be a party and that people will be watching me be Sylvie and that they might hate it. Or maybe they’ll love that first episode, the one where I dance on the counter, and they’ll love the next ones, too. They’ll love them all up until they get to the ventriloquist’s dummy episode.

I feel those knots forming — the orange-Swish knots, the dancing-on-the-counter knots, the mudslide-in-Canada knots — and I know I have to find some way to figure this out. I only have two more nights before I have to choose the perfect wax museum person, and I only have two more nights to get this whole ventriloquist’s-dummy thing right before taping or else all will not go well and none of us will have jobs next season and Sylvie will never, ever get glasses.

I wake up and I am still mad about Elinor’s yellow flag. Still mad at Mr. Lamb-and-Peppers Santorini, who is no fun and doesn’t think anything’s funny and who thinks jumping jacks are a good idea right after you’ve eaten hot chicken and rice at lunchtime.

“Why so stormy?” my dad asks. I almost act even more stormy when he asks this but then I think of Elinor and remember that I am happy to see my dad when I wake up every morning and happy that he cares if I am stormy.

I give him a hug.

“MUCH better,” he says. “Wow. Did you see that, Big Henry? That deserves a pancake.”

“Will it have flaxseed in it?” I ask, squinting. Not a hoping-for-glasses squint, but a hoping-there’s-no-flaxseed-in-my-pancakes squint.

“Yep,” he says. I groan. “And chocolate chips.”

“Yes!” Big Henry and Mommy say at the same time.

“Jinx!” I say. But then I release them right away and get back to being mad at my very mean teacher.

“Who are you going to choose for the wax museum?” my dad asks.

“There’s no one just right. I don’t have a thing,” I say.

“A thing?” my dad asks.

“Like you have cooking,” I say. “And Mommy has art, and Teddy has science, and Elinor has sports and being English.”

“You have acting,” he says.

“But not the kind of acting they like for school projects,” I say.

“Why don’t you tell your teacher the problem and see if he can help?” my mom says.

“No way, José,” I say, then I tell them the whole story of yesterday to make them understand.

“Why didn’t anyone explain the situation to him?” my mom asks. “That’s where you need to use your voice.”

I eat my pancakes and think about this. I picture myself with an old-fashioned megaphone screaming “WE WERE JINXED!” at Mr. Santorini. “What if he gives me a yellow flag for using my voice?” I ask.

“He won’t,” my dad says.

“He might,” I say.

“Not if you’re polite,” my mom says. “I promise.”

“I wish I had a script for life,” I say. “I would do so much better at it.”

“We all wish that,” my mom says.

“But parents always know exactly the right thing. I feel like you did get a script.” My mom and dad smile at each other.

“Um, no,” my dad says. “Thankfully, you only remember the good things we say.”

“So far,” my mom says.

“Time for school!” Big Henry says, shoving some Legos and stuffed animals into a bulging backpack.

“You can’t bring all of that to school,” I say.

“I want to use it in sharing time,” he says.

I feel mad at him for having sharing time with Ms. Kim when I have to go face that cuckoo Mr. Santorini and his Hawaiian shirt and his completely and totally unfair behavior chart. I give him a little extra push out the door, which I’m glad my mom doesn’t notice.

Today at library time, I feel mad from the second I walk in, especially when I see Charlotte and her glasses with her nose in a biography of Julie Andrews. This reminds me of second grade, when Charlotte was trying to be bossy Maria von Trapp in the moving-up play, and now I’m thinking, Oh, so she’s going to be Maria von Trapp and isn’t that just perfect?

“Jules, I’ve got it!” Elinor says. Of course she’s got it.

“Who?” I say, but I kind of don’t want to know.

Everyone has someone perfect to be except for me.

“I’m going to be Jackie Robinson,” she says. “He’s a baseball player — a very important one.”

“He?”

“Yep,” she says.

“Perfect!” I say. She is the exact person who could do a boy character as a girl, which makes me jealous, so I’m kind of acting but Elinor doesn’t know this. Almost-invisible lie number three.

I flip through pages and pages of people who did lots of interesting things but none of them have anything to do with me — they have to do with baseball and science and history and it all sounds very serious and important. I stop for a minute at Elvis Presley and imagine my dad singing “Teddy Bear” into his spatula, and then I think of myself dressed up as Elvis in Jailhouse Rock, with jail clothes on and a guitar. And when people push my wax museum button, which will be made out of a soda-bottle cap and painted silver, I will say in a slow Southern accent, “I’m Elvis, ma’am, the King of Rock ’n’ Roll.”

I think my dad would be proud of this and I think it would be fun to slick my hair and wear a jail jumpsuit. I can kind of picture myself doing it well, maybe even really well — the same way I can actually picture myself playing the dummy really well. I’m just so afraid to try. I put away the Elvis book and put a Post-it inside my brain for when Big Henry does the wax museum. He’d be a perfect Elvis. He’d probably be a break-dancing Elvis, which would make the best wax museum biography ever, and he would be famous because that’s just Hank — he’s likable and entertains people without even thinking too much about it. Having things be easy is his thing, I think.

“Elvis?” Charlotte says, laughing.

“I’m not being Elvis. I was just looking,” I say.

“I think you should,” she says. “I think Elvis would be perfect.”

I feel my heart start pounding because I think Charlotte is making fun of me or something.

“It would be so funny with your hair slicked back and a big funny suit and a stand-up microphone.” And now she’s laughing, and so are Elinor and Teddy, and I just feel like everyone’s making fun of me.

“Why don’t YOU be Elvis, Charlotte! You’re the girl with the big, loud voice about everything. You be him. You’d be better at being him than you would at being Julie Andrews!” Then Charlotte runs

out of the library and Elinor and Teddy are staring at me.

“Jules,” Mr. Santorini says, and I know before I even turn around that he is shaking his head and that head-shaking is the thing that comes right before a yellow flag. This is the what-if I’ve been dreading.

I decide to use my voice. “Did you know that tubers are really just root vegetables, like potatoes?”

He squints at me, but I go on. “Could be a white potato or a sweet potato, or maybe a radish —”

“Jules, why is Charlotte crying in the hallway?”

I shrug.

“You have no idea? You don’t think it has anything to do with you yelling at her?”

How did he see me yelling at her but not her making fun of me? It’s the same way he saw Elinor push Teddy but did not see that we had been jinxed by Teddy in the first place. I really think he might need glasses! I feel that popping-popcorn feeling in me and I want to run into the hallway, too.

I know I have to use my voice to say what happened since he didn’t SEE what happened, so I do. I let it all out. I tell him that all the jumping jacks he has us do make me nervous, that the behavior chart makes me even more nervous, that Elinor was only trying to get Teddy to release the jinx, that Charlotte was making fun of me, that she always gets everything, and that everyone has a thing except for me. I tell him all of those things and I say them fast in case he stops me with a Captain von Trapp whistle he’s been hiding in his Hawaiian shirt. I would not be surprised.

I am afraid to look over at Elinor because I have the feeling she will be mad that I brought up her yellow flag all over again since she likes to handle things on her own. And now I’m wishing I hadn’t said anything since Teddy could get in trouble for jinxing us. But I don’t even know if that’s possible because I don’t understand the rules of the behavior chart in the first place. I feel a little dizzy.

“Sounds like we need to step outside,” he says.

“For jumping jacks?” I say. But he doesn’t say anything to this and I know from my own parents that when they don’t say anything, they are really mad.

Starring Jules (Super-Secret Spy Girl)

Starring Jules (Super-Secret Spy Girl) Starring Jules (third grade debut)

Starring Jules (third grade debut) Starring Jules (In Drama-rama)

Starring Jules (In Drama-rama) Izzy Kline Has Butterflies

Izzy Kline Has Butterflies Starring Jules (As Herself)

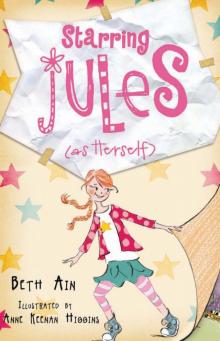

Starring Jules (As Herself)