Izzy Kline Has Butterflies Read online

Page 5

the other day.

I have been sent to the principal’s office,

on principle.

Where are you off to?

Have you been to Saint Maarten?

No? It’s gorgeous this time of year.

Just what the doctor ordered!

We all need a break, right?

Not the kids—us!

This is how the parents talk at the supermarket

while I decide which gum to chew on our trip to

Florida—

Juicy Fruit!—

while Mom smiles and asks questions about places we

will never go,

because when she takes a vacation, she wants to be

with her mom,

with sunglasses

with a good book on a beach,

where she can

just be.

I love it too, starting

with the music that plays when the baggage claim

starts up and spits out bags, one at a time—

tropical music that welcomes you to a place so friendly

the warm air hugs you

when you walk out into the night.

Welcome to Fort Lauderdale.

We spend time at the beach,

at Nana’s pool,

reading good books,

being

with each other and by ourselves

while James spends time with his music,

sharing it with us only when the volume is turned up

so loud his headphones vibrate

with the extra sound.

I don’t think he heard the tropical music at the

baggage claim or the quiet

in the car rental garage at the airport,

or the waves or the kids—

over there!

They must be five or so

making a tunnel that will collapse into itself later on

at high tide.

I sit with my legs straight and try to bury them

myself.

No luck.

I throw a flip-flop at James, and he startles and gives

me a what the—? look.

BURY ME, I mouth.

He ignores me, closing both eyes and then opening

one back up.

I pout.

He throws off his headphones and his bad attitude

and gets burying.

I win! I am five years old again and he is ten.

Now it’s the sand that’s hugging me,

and my brother,

and the waves break,

and the sand

laid thick on top of me

breaks,

freeing me,

like this break from the end of winter,

the beginning of

spring.

The minute we get back, we have to finish up our

Colonial Fair projects.

I made a diorama from one of James’s giant

shoe boxes.

It is a colonial classroom.

Mom and I went through my dollhouse for wooden

things, got chalkboard paper at a craft store, made a

classroom that made me think of

Little House on the Prairie.

We brought in our dioramas yesterday and we

oohed and aahed at each other’s handiwork.

Some of the boys used Legos, and I felt jealous of their

modern little boxes.

Today, at the Colonial Fair, we will stand by our

dioramas,

dressed in character,

and present our reports to the other grades.

I will be a teacher—

a colonial teacher.

It’s easier to think about what you might have been

than what you’ll be.

I need a bonnet!

I say to my dad in the morning.

I forgot about the bonnet, I say,

careful not to seem upset.

I have my dress and my apron, I say.

I want to cry but don’t want him to be mad that these

things only happen

at his house

on his night.

Dad goes into a closet in his apartment,

his apartment that echoes when you take steps on the

hardwood floors,

echoes when you make a phone call late at night

to your mom.

He pulls out a snow hat with flaps for the ears.

No thanks, I say, scrunching up my nose.

It snowed a lot then, he says. The winters were hard.

I think this is more interesting than a bonnet, he says.

Be the girl in the snow hat, he says.

Let the other girls be the ones in the bonnets.

I carry the hat in my lap in the backseat of the

sports car.

I carry it in my hand,

behind my back,

when I walk into the classroom.

I watch all the other girls put on their bonnets.

Did you forget yours, Isabel? Mrs. Soto asks.

I’ve got plenty of extras, she says.

Mrs. Soto is very excited about the Colonial Fair.

I think she would have been a teacher back then too.

No, I say. I’ve got a snow hat,

with earflaps.

The winters were hard, I say.

Even better than a bonnet, she says.

Kids from other classrooms come to each station,

and I tell them all about my colonial classroom.

I wear my hat the whole time

and Quinn stands next to me in her bonnet,

barely talking.

She’s a nurse, so I think maybe she’s being quiet so her

diorama patients can rest.

She says she’s cold.

I’ve got a snow hat, I say.

Trade ya! I say.

She can be the girl in the snow hat now.

I’ll be the one in the bonnet.

I am hyperventilating.

I cannot breathe.

I cannot talk.

I ran so fast I wished the gym teacher could have seen.

She should have given me a reason to run

in the first place,

and I would have passed those phys ed tests

with flying colors.

Today I would pass.

Today I would be the best.

Help!

Running and yelling even after the teachers came,

even after the nurse came,

even after the ambulance came.

All because,

before she was in the fourth class,

before she ever lived here,

Quinn was in

and out

of a hospital

for a year.

I am still out of breath.

But I do not have asthma.

Neither does Quinn.

It is something else.

Cancer.

Or it was.

Before she was my new favorite person,

she spent most of her time throwing up the horrible

medicine that is supposed to kill the cancer but it kills

everything else too, everything in sight.

Even the good stuff.

Even the stuff that helps you through cold season,

says the poster in the pediatrician’s office, warning

nervous parents not to ask for antibiotics.

Obviously, my dad muttered

at that poster,

annoyed at it or at me

the only time he ever took me there without Mom,

his doctor-ness showing up also for the first time.

He hides it otherwise, pretending he is something else,

in some other business where no one asks you for

advice.

She’ll have some tests, Quinn’s parents are saying now

to the nurse,

; who is worried sick.

I am dizzy still.

I tried to catch her, but she fell in a heap

off the thing that spins so fast

I’ve seen more than one person actually throw up

from it.

The moms worry about the spinning and maybe

someone getting hurt.

I only worry about the throwing up.

Until now.

Until I saw Quinn Mitchell, bossy and smart and

excellent at building and planning and being a

president,

fall in that heap, eyes rolled back.

She’s going to be okay, her mother said to me.

She’s run-down.

We’ve been through this before.

If we have to do it again,

we will.

I wish I could call my dad,

but he’d stay quiet, probably

pretending not to be a doctor.

Are you okay, honey? Quinn’s dad asks me as they

wheel Quinn away

on a stretcher.

She is awake and she smiles at me.

I smile back.

Yes, I say.

I am pretending too.

I don’t tell anyone at home what happened,

don’t tell them I was there,

that I heard all about the cancer

that they pretended was something else.

Something with a long name and an abbreviation that

is supposed to make me think it isn’t terrible.

I go about my business, as they say.

I do my nightly reading log.

Stargirl keeps me company.

I had thought it was over between Stargirl and me

until Quinn told me there was a sequel.

And now we’re together again and I partly want to

read it fast and I partly want to read it slow, since all

that’s left after this is the Stargirl journal,

which is just a place to write,

and all you really need for that is your head

and a piece of paper.

But I will get the journal for Quinn for her birthday,

or maybe

for a get-well-soon present, because we love Stargirl.

We.

Quinn and I.

Quinn and me.

Are we best friends? We never discussed it,

never had a real no-friend club meeting.

I don’t even know when her birthday is.

I will get her the journal anyway, and I will write a

note on the inside,

the way my grandmother does when she buys me

a book.

With so much love,

Grammy.

Mine will say:

To the great Quinn Mitchell, president of the no-friend

club, in charge of everything,

Love, Izzy Kline, vice president, in charge of entertainment.

I would like to write best friends forever also, but I’ll

decide about that later.

I practice it in the margins of my reading log.

Love, Stargirl

45 minutes

pages 91–128

best friends forever.

There is another person in the fourth grade who can

sing and it is not Quinn, since Quinn isn’t even here

to audition.

It is Lilly with two l’s.

Turns out Lilly loves the play as much as I do because

she gets the best part,

the part I kind of wanted.

Kind of with all my heart.

There are a couple of solos in the show, and I got a

teeny one, a small part of a small song called “Glad to

Have a Friend Like You.”

But I am not glad.

I want the one Lilly with two l’s got and the whole

way home I think

Oh, everyone just LOVES LILLY, all of a sudden.

LOVES LILLY’S PERFECT VOICE.

LOVES THE WAY SHE SINGS WITH FEELING.

I’m shouting these things in my head all the way home,

shouting so, so loud in my head.

And I am so, so MAD,

I run into the bathroom and I throw up.

I thought I maybe made myself sick

with all that head shouting.

But I did not.

Unless jealousy can also cause a fever.

Because I threw up, Mom is nervous.

She even calls my dad to see if maybe,

possibly,

he could stay with me.

But that would mean rescheduling patients, he tells her.

But the smell—she says.

I’m not sure I can handle—she says.

I am a patient to my mom, who is impatient herself

with Dad

and his hanging up quickly.

I can tell by the way she holds the phone to her ear

even after he is gone.

But the throwing-up part is over anyway, and now it

is the soup-and-TV part,

the part Mom is really good at,

the part where she puts on old shows on the classic

channel and we watch them all,

and she talks about her days off from school as a kid

and we play hangman

and color old coloring books

and she introduces me to Bewitched,

a show where the mom is a witch who can do

all kinds of things just by wiggling her nose and it’s

kind of a terrible show but it makes her smile

so we watch a marathon and color.

Ding, dong.

Mom and I look at each other because no one ever

rings a doorbell unless they have been invited or food

has been ordered.

I feel a little better, I say, getting up but not really

wanting to get up out of our cozy corner of the sofa,

not really wanting to feel all better,

just a little better, because it would be so nice to have

one more day like this.

Old shows and Lipton soup and laughs that make

those sore throw-up muscles hurt,

and flowers.

The doorbell is a flower delivery.

Something that doesn’t smell like throw-up.

Love,

Dad.

It’s easy to forget because he is so organized and

serious and because he loves art and classical music

and also jazz, which drives my mom crazy,

that he is also funny.

Flowers from Dad, I say.

He’s good at flowers, my mom says.

I put the flowers on the table. Our flowers.

I plop back down into my spot but have to get up

again, almost immediately.

The flowers are blocking the view of Bewitched.

The flowers that should really be for someone who

needs them.

If only I could just wiggle my nose, I think.

As you may have heard, fourth grader Quinn Mitchell

was taken to the hospital by ambulance this week after

falling ill on the playground, it says.

The Mitchell family has asked us to communicate on

their behalf. Quinn is a fighter, it says.

She has battled and won the fight against acute

lymphoblastic leukemia once before, and if that is the

diagnosis,

if this is a relapse,

we are certain she will win again, it says.

In the meantime, we at the PTA encourage you to

communicate with your children about their feelings

and concerns. We also encourage you to please keep the

Mitchell family in your thoughts while they investigate

the cause of Quinn’s current condition.

> Mom looks at the paper and looks back at me.

Oh, honey, she says.

I’m fine, I say, taking the paper back from her.

The paper she found in my folder, and which she was

looking for because another mom had already called

about it.

She’s fine, I say, tucking the paper back into the pocket

of my folder,

the folder I picked to be my take-home folder for the

new school year.

The one with puppies on it

that was going to cheer me up each day about having

the yelling teacher and

Lilly with two l’s and no one else.

It’s going to be fine, I say.

I think we should talk about it, Mom says.

I think I have a lot of homework, I say.

I give her a big, wide smile and I nod a big, slow nod

to let her know

I have not lost my sense of humor.

It

is

going

to

be

okay,

I say slowly

and loudly.

As if she doesn’t speak English.

As if I know it for a fact.

As if I am a grown-up,

a member of the PTA,

writing letters home about things I know nothing about.

Lilly and I stand side by side today,

the day after my sick day

the day after

the day after

she got the part I wanted.

The day after my mom found out that Quinn had

collapsed.

When Lilly belts out

“When We Grow Up,” I understand completely

why she got that part and

I don’t feel sick about it anymore.

I will be part of the chorus.

I will say my “Glad to Have a Friend Like You” lines

with gusto,

because I’m glad not to be throwing up anymore,

glad to have a part,

glad for my friends in the no-friend club,

and our president,

in charge of everything,

who I will gladly stand next to at the show,

which is turning out to be more of a concert

anyway—

with us standing

in rows

on the steps

of the stage.

Little groups of us will take a place on the stage

in the spotlight

for the acting parts or for the solo parts.

Lilly and I whisper to each other as we practice,

as others practice—

Fiona and Sara and the Candy Land party girls dancing,

a group of girls doing a skit to “Girl Land.”

The whole group clapping through “Sisters and Brothers.”

The funny kid who speaks the

“Don’t Dress Your Cat in an Apron” part

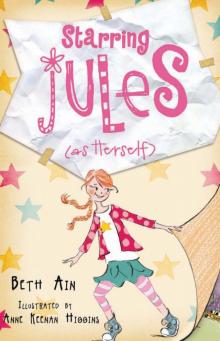

Starring Jules (Super-Secret Spy Girl)

Starring Jules (Super-Secret Spy Girl) Starring Jules (third grade debut)

Starring Jules (third grade debut) Starring Jules (In Drama-rama)

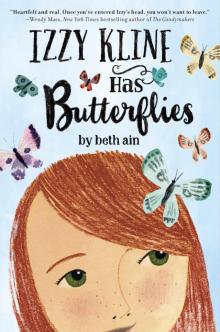

Starring Jules (In Drama-rama) Izzy Kline Has Butterflies

Izzy Kline Has Butterflies Starring Jules (As Herself)

Starring Jules (As Herself)